The results of Michigan’s Democratic presidential primary were just messy enough that both sides could claim victory. But there was a clear warning for President Joe Biden from key elements of the Democratic coalition.

More than 100,000 Michiganders took the time to vote for nobody instead of the incumbent president. In a battleground state Biden won by fewer than 150,000 votes in 2020, the strength of that protest vote sent an unambiguous message. And look a little deeper at the communities where those votes came from, and the results reveal significant weaknesses in his electoral base among Arab American voters (a potentially pivotal bloc in the state) and young voters (a key part of Democrats’ coalition everywhere).

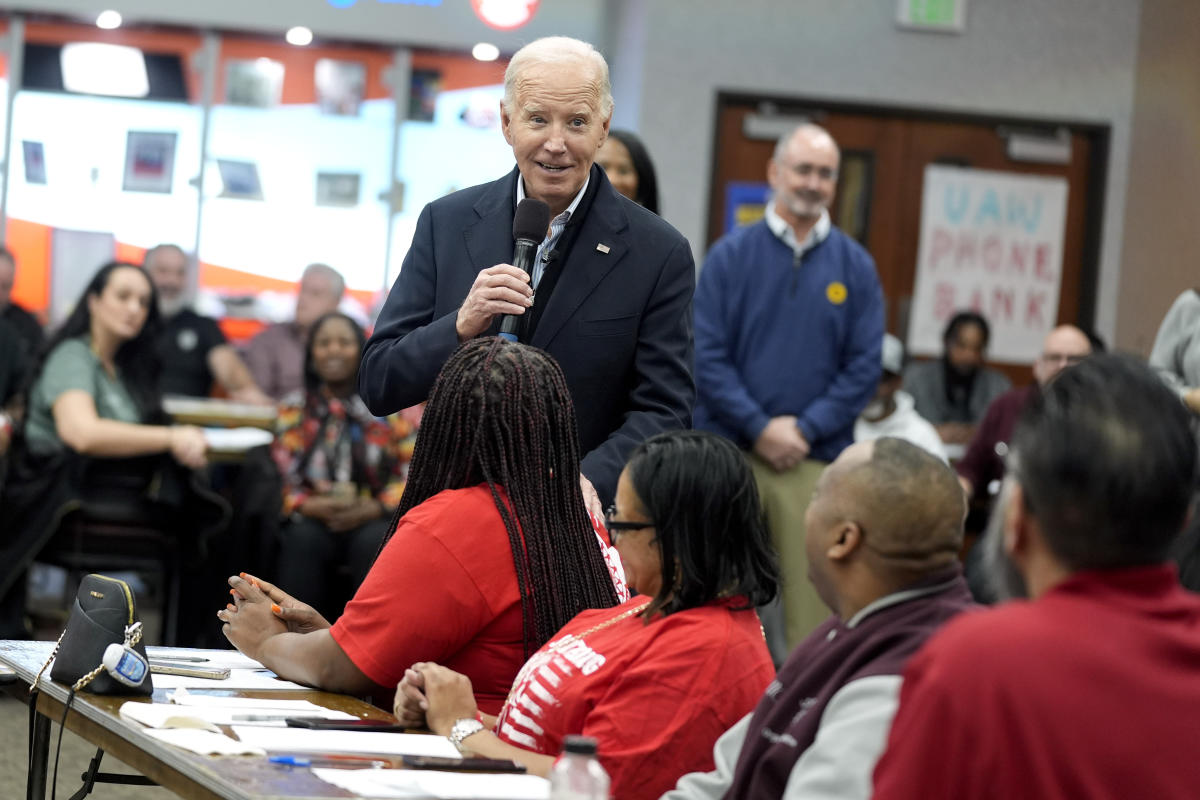

Amid the debate over whether the “uncommitted” campaign was a success, however, was a reminder that Biden remains the overwhelming choice of Democratic primary voters. He earned greater than 80 percent of the vote in Michigan. And his success was driven in part by continued support from Black voters, who backed him over “uncommitted” and are poised to assert themselves in a number of Super Tuesday states next week that will place the president on the cusp of clinching his party’s nomination without facing any significant challenge.

Biden’s likely November opponent, meanwhile, has his own holdouts to worry about. Former President Donald Trump won another convincing victory on his path to the GOP nomination, but he continued to show signs of weakness among suburban voters especially.

Whether the two candidates are able to shore up the support of their party’s holdouts — or perhaps manage to draw from each other’s — will help decide the White House. It’s true that both Biden and Trump are dominant in their parties, but a deep dive into the Michigan maps underscores the vulnerabilities now that could haunt them in November.

Arab American voters and young voters pushed back — and highlighted the fragility of Democrats’ coalition

Arab American communities who have been heavily critical of Biden in recent months — arguing he should publicly call for a ceasefire amid the Israel-Hamas conflict — drove the strength of the uncommitted vote on Tuesday. Organizers with the “Listen to Michigan” campaign, backed by Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) and former Rep. Andy Levin, among others, actively campaigned to persuade Democratic primary voters to vote uncommitted as a way to send a message to Biden favoring a ceasefire.

“Uncommitted” received a majority of votes in Dearborn and Dearborn Heights, and got more than 60 percent of the vote in the smaller city of Hamtramck, an enclave of Detroit with significant Yemeni American and Bangladeshi American populations.

Precinct-level results further show the strength of the uncommitted campaign among Arab American voters: the protest vote got more than 90 percent in Dearborn’s neighborhoods that are heavily Arab American.

Turnout was also good in the places where the uncommitted vote was strongest, suggesting the Biden critics were particularly motivated to show up to mark their anger. Statewide, about half as many ballots were cast in this year’s Democratic contest compared to the party’s competitive 2020 primary. In the Dearborn precincts where the uncommitted vote dominated, turnout was roughly three-quarters of the total from four years ago.

The uncommitted campaign also showed strength in a handful of precincts surrounding college campuses, suggesting significant protest votes from young voters, who polls show disapproved of Biden’s handling of Gaza most compared to other age groups. Nearly one in five voters, 19 percent, voted “uncommitted” in the city of Ann Arbor, home to the University of Michigan, and the protest vote won outright in a precinct covering part of the college’s campus. It also got 17 percent in Ypsilanti, home to Eastern Michigan University.

To what extent uncommitted voters come around for Biden in the general election will depend in part on how the incumbent responds to the ongoing challenge of the Israel-Hamas war. Arab American voters are a pivotal voting bloc in Michigan, while young voter turnout will be key for Biden in every battleground state. And Tuesday’s result in Michigan was clear: The coalition that the Democratic president would rely on for victory includes voters who are currently skeptical of him.

‘Uncommitted’ had few other strong points and was weakest in majority-Black areas

The flip side of the uncommitted vote’s localized strength was that it made little splash in much of the rest of the state. Outside of the strongholds of Arab American and young voters, “uncommitted” received comparable numbers Tuesday to the 10 percent of voters who voted uncommitted in 2012, when then-President Barack Obama was running as an incumbent.

That suggests that Biden’s troubles largely did not extend to other key constituencies in the state, including Black voters who powered his 2020 general election victory.

In fact, uncommitted performed especially poorly in majority-Black areas. In Detroit, a Democratic bulwark where running up the score will be key to Biden’s general election chances, uncommitted got just 8.7 percent of the vote. In Flint, less than 6 percent of ballots went for uncommitted; in Southfield, just 5.6 percent did.

Democrats have worried for years about declining Black support and especially in recent months about polls showing drop-offs in Black voters’ enthusiasm for Biden. But while primaries tend to bring out the most highly engaged voters, the president’s performance Tuesday at least signals that he has not lost that core of his base.

Trump dominated again, but Haley showed his continued weakness in the suburbs

Trump ran up the score overall, demonstrating continued strength in blue-collar places like Macomb County, where he won 75 percent of the vote.

But as in South Carolina this past weekend, Trump was weakest in Michigan’s suburbs and other affluent parts of the state.

Nikki Haley, the former U.N. ambassador, didn’t win any of the state’s 83 counties, but she did hold Trump to under 60 percent in Washtenaw (50 percent) and Kent (59 percent) and nearly did the same in Oakland (61 percent). Haley won a few individual towns in these counties, like Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti in Washtenaw, East Grand Rapids in Kent and Birmingham in Oakland.

These are exactly the types of places where Trump has struggled since 2016, and the results from the first primary contests underscore that these voters remain opposed to his political comeback.

In traditionally Dutch Protestant Kent County, for example, Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in 2016, but the county flipped four years later, with Biden carrying it en route to flipping Michigan back to the blue column.

The 34 percent of the county’s voters who supported Haley on Tuesday will be targets for the Biden campaign in the general election. And on that front, the primary numbers may be a good sign for Biden: The “uncommitted” voters are a danger for Biden in that they may vote for a third-party candidate or stay home, not that they’re likely to go for Trump.

Voting changes have boosted turnout, making comparisons complicated

“Uncommitted” breaking 100,000 votes was eye-popping, but there is some important context that might temper any overreaction.

More than most states, Michigan has liberalized its voting laws in recent years to encourage increased voter participation. The state in 2019 implemented automatic voter registration in which citizens are registered to vote when they renew their driver’s licenses unless they opt out. The 2020 election was Michigan’s first with no-excuse absentee voting, and the state has since added more dropboxes for mail ballots.

The changes appear to have had a tangible effect on turnout.

When “Uncommitted” received 11 percent of the vote in Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign, it did so with fewer than 21,000 votes. The result on Tuesday was only 2 percentage points higher, but with nearly five times the raw vote totals.

That’s followed the recent trends: Turnout in the general election rose sharply from 2016 to 2020. And it was flat from the 2018 midterms to 2022, defying a national trend of decline despite having the same marquee Senate and governor’s races on the ballot in both years. That makes raw vote comparisons — like the “uncommitted” totals from 2012 versus 2020 — to previous elections difficult.